|

|

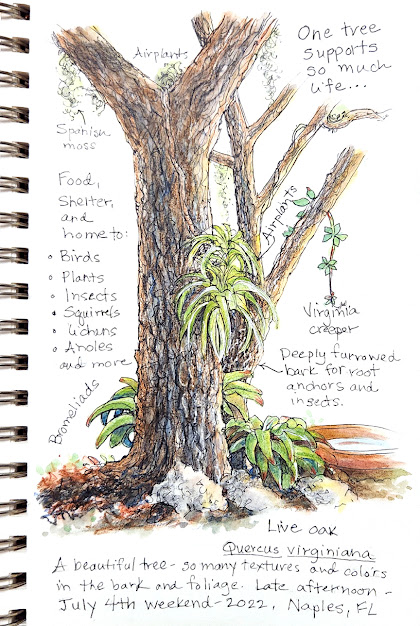

New and old Live Oak leaves in late spring. |

It all started with oaks.

Some time ago, I sketched a favorite tree and wrote about oaks as akeystone species, and why fallen leaves are important to their habitat. I’m much more aware of leaf cycles now. In my neighborhood and beyond, live oaks dropped

their tired leaves this spring and new leaves emerged, bright and sassy. As we move into summer they’re turning a

darker, more sedate color. Deciding on

the actual color of live oak leaves is a challenge for me – as a whole, tree

foliage seems to be a muted dark olive at times; other times there is a hint of

blue in the green. Up close they

vary. Besides enjoying the puzzle of how

to accurately sketch leaf colors, I’m looking at fallen leaves and all the bits

and pieces that make up the leaf litter under trees.

Treasures under the oak tree.

I’ve been reading learning about the value of fallen leaves

to ecosystems in general and realize this is an invisible chunk of the natural

world I often overlook. Yes, I know that

leaf litter is important, but until I started to educate myself more deeply, I didn’t

realize how vital it is to the health of food chains. In practice, I let fallen leaves lie (in most

places) most of the time, unless they pose a fire risk. But now this industrious hidden world kindles

my curiosity and wonder. Imagine! An entire food web depends on the untidy clutter

of nature’s litter.

Natural litter (as opposed to human litter) is

organic material such as dead leaves, twigs, branches, seedheads, husks,

berries, and grasses. We can find leaf

litter on the forest floor, in streams, rivers, and bays, and under our

cultivated trees and shrubs (if not raked away). In my backyard

litter, I’ve seen earthworms, mushrooms, spiders, beetles, millipedes, cicadas,

snails, ants, caterpillars, anoles, centipedes, toads, grubs, crabs, and small

snakes, not to mention MANY unidentified insects. Fungi loves leaf litter too – mushrooms, puff

balls, and bracket fungi often make their home there.

Leaf (needle?) litter under the slash pines. Pine needles are actually modified leaves.

Besides sheltering many species, this leaf layer conserves

moisture and protects the soil below. Vulnerable

creatures can find a home or a hiding place from predators. Some moths make cocoons that mimic the same dried

leaves they nestle into for their change from caterpillar to moth. A small snake or anole can quickly and easily

vanish into the leaves or brush piles.

Litter hangs around a while, decomposing slowly through the action of

weathering and digestion. Temperature

and humidity affect the decaying process, and all sorts of living things feed

on (and excrete) the nutrients locked inside.

Living in the leaf layer are small consumers that also de-construct

– they help break apart larger bits such as leaves, twigs, branches, and

berries. A wide variety of worms and

insects make their homes in the earth below, some for their entire lifespan. Cicadas spend years underground before

emerging to mate. Underground dwellers

aerate the soil as they burrow and leave their waste for others to feed

on. Bacteria and underground fungi

further decompose the smaller bits into nutrients that feed the plants and

trees that initially produced them.

These tiny life forms are part of the base of our food

webs. Dr. Doug Tallamy, author,

entomologist, and conservationist, reminds us that "All animals get

their energy directly from plants or by eating something that has already eaten

a plant. The group of animals most

responsible for passing energy from plants to the animals that can’t eat plants

is insects.”

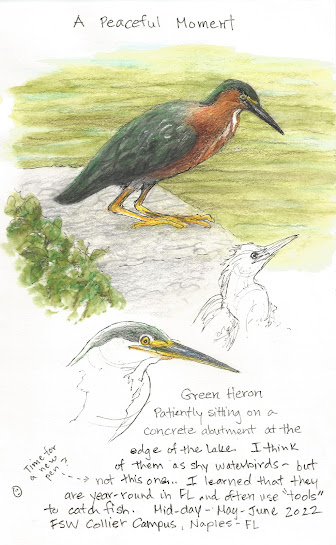

For example, birds forage for insects and worms and other

edibles among decaying leaves. For many

birds, this is their primary source of food.

Just think of the larger life forms that depend on birds for their diet

and so on up the food chain – and it all starts with plants and their litter.

We have a lot of thanks to give to the many thousands of (or

more) insects and other invertebrates that make their homes in the ground and

the decomposing layer of litter covering it.

Every minute, they’re busy tidying up and transforming raw material into

usable energy. It may have been the oaks

that started it, but there are so many more species contributing their own

litter. I’m more careful now about

raking away the leaves, pine needles, twigs and such, and find myself checking under

every tree and bush for a glimpse of that mysterious underground universe.

For more exploration:

University of FL/IFAS blog, an interesting read on the value

of leaf litter in Florida:

https://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/wakullaco/2015/01/17/leaf-litter/

“Life in the Leaf Litter” from the American Museum of

Natural History, a downloadable PDF booklet with engaging text and

illustrations:

https://www.amnh.org/content/download/35188/518925/file/LifeInTheLeafLitter.pdf

Things that go squirm in the night... a 3 minute video from

ChooseNatives.org:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VKFzilm3Rwk

Slash pine litter coloring page: download a PDF.

Media

Aquabee sketchbook, 6x9”

.7 mm mechanical pencil

Pitt Pen, Sepia F and Micron Pigma, black 01

Mondeluz watercolor pencils

Niji waterbrush, Medium